By Paul Post

A prominent environmental group and the state agency charged with protecting Lake George have partnered for many years on programs designed to kill Eurasian water milfoil, an aquatic invasive species that causes environmental problems and hurts the economy by impacting recreational activities such as boating, fishing, swimming and paddle sports.

But the Lake George Association and Lake George Park Commission are at odds over the recent application of the chemical ProcellaCOR in two bays in northern parts of the lake.

The product, made by Indiana-based SePro Corporation, kills plants with a hormone that plants absorb, causing them to grow too rapidly and die off within a few weeks. The chemical has had positive results in numerous water bodies across America and locally in places such as Minerva, Brant and Saratoga lakes, Lake Luzerne, and Lake Sunnyside and Glen Lake in Queensbury,.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency approved ProcellaCOR’s use in 2017 and the state Department of Environmental Conservation okayed it for New York in 2019.

“We’re not against the use of ProcellaCOR generally,” said LGA Chair John E. Kelly III. “It’s not like we’re against using chemicals for invasive species. Clearly in small lakes and ponds that are being overrun I would not argue against using it. But ProcellaCOR’s label says it’s meant for still and quiescent water with no major outlet. Lake George is different.”

Kelly, a former IBM executive and current RPI board chair, is also founder and still a key advisor to the Jefferson Project, created 11 years ago to gain a better understanding of threats to Lake George water quality. The program has provided extremely detailed, valuable information using some of the world’s most advanced science and technology.

Blair’s Bay and Sheep Meadow Bay where ProcellaCOR was applied have significant currents, he said. The chemical could be swept elsewhere before it works and settle in deep water without much sunlight, which is needed for the chemical to break down. Without this process, ProcellaCOR might even act like a fertilizer and cause unwanted plant growth, he said.

“We’re not being overrun by Eurasian water milfoil like some of the shallow lakes,” Kelly said. “We don’t have a crisis. It’s just not the right time and place. Nobody knows the long-term impact. Lots of chemicals thought to be good end up being not so good over time. The bottom line is, why do an experiment in Lake George?”

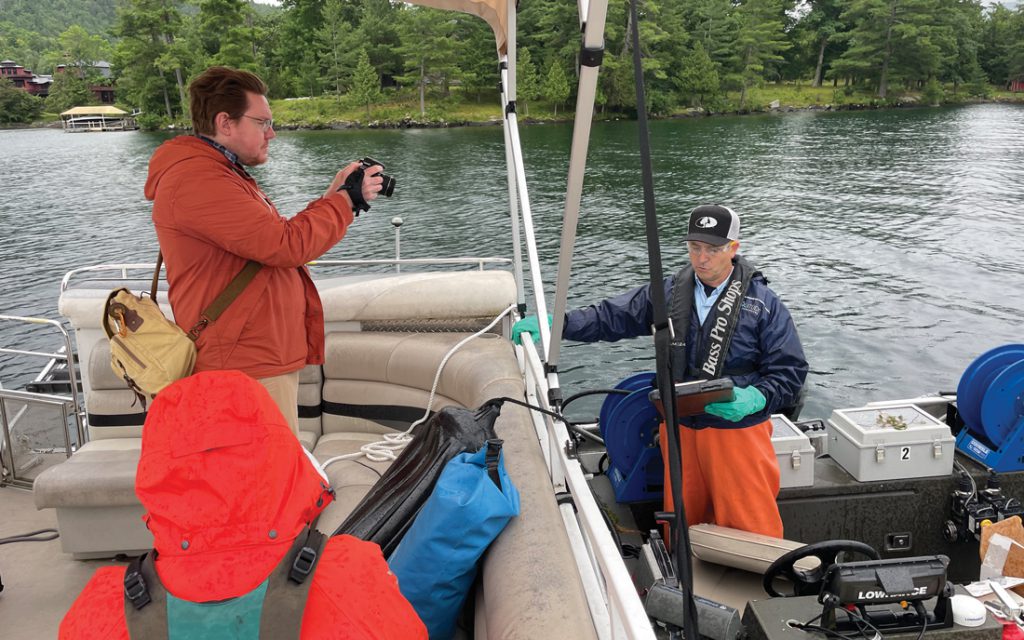

But Park Commission Executive Director Dave Wick said the applications are already showing extremely positive results at considerable savings from the traditional DASH (diver assisted suction harvesting) program, which costs about $400,000 annually.

The LGA contributes $140,000 annually and offered to pay for hand-harvesting at Blair’s and Sheep Meadow bays to avoid ProcellaCOR’s use.

However, Wick said ProcellaCOR is a new tool in the toolbox that should be used at sites where milfoil is densest and grows back after hand-harvesting, which he likened to lawn mowing. In some lakes, milfoil has been almost completely eradicated after ProcellaCOR’s use.

“The commission has never called milfoil control in Lake George a crisis,” Wick said. “However, we do spend close to a half million dollars every year for a program we do (DASH). We’ve had many bays in Lake George, year after year ripping up all the plants, creating turbidity, releasing phosphorus from pulling up plants.”

“If we can control milfoil more effectively with less impact to the lake at a cost that’s less than we currently pay, why wouldn’t we try that and utilize it in situations where we have difficult milfoil populations?” he said. “The treatment sites have responded exactly as predicted. There is no remaining viable milfoil. You can’t even find any milfoil plants and all of the native plants are robustly living.”

This year’s ProcellaCOR treatments cost $18,600. If milfoil doesn’t grow back, the savings will compound next year and beyond.

About a dozen years ago, some bays were completely overtaken by milfoil, Wick said. “In one four-year span we spent over $2 million hitting those sites over and over and over again,” he said. “We got the numbers down to where we can just be in there a few days now (hand harvesting), but at what fiscal cost?”

Wick said hand-harvesting will never be phased out. At some locations, milfoil can be controlled with a just a few days’ work.

But he said the commission is considering ProcellaCOR’s future use at especially problematic sites, which might include Sunset Bay near Huletts Landing and possibly Harris Bay near Cleverdale.

“ProcellaCOR does not disturb the sediment or native plants or macro invertebrates,” he said. “It is really much more effective. We just have to use it in situations that really warrant it. We spend a lot of time working on this program and evaluating all these factors.”

“All of the science and verified treatment results all support ProcellaCOR’s safe and effective use,” Wick said. “We want to know if there’s a problem with this, but we haven’t been able to find any such science or any record that shows anything other than safe or effective.”

The LGA, towns of Hague and Dresden, and several property owners took legal action that blocked ProcellaCOR’s use in Lake George for two years, until this June 28, when Warren County Supreme Court Justice Robert J. Muller lifted a temporary restraining order, allowing the Park Commission to move forward. Adirondack Park Agency also approved the chemical’s use.

But Lake George isn’t the only place where heated battles over ProcellaCOR have occurred. In July 2023, the state of Vermont denied a permit for its use in Lake Bomoseen, the largest lake within the state’s borders, in the wake of public outcry from towns and residents around the lake.

Kelly said the LGA, with Jefferson Project’s state-of-the-art resources, is closely monitoring the recent ProcellaCOR applications in Lake George.

“We have incredible data on the water movement at the minute they were applying it; what transpired during and after the treatment,” he said. “We are now collecting all that data, analyzing it, and will issue a preliminary report in a couple of weeks including visuals and scientific measures of the plant species on defined grids. This hopefully leads to good healthy discussion about whether we should do it again or not.”

“If I and the LGA were wrong I’ll be the first one to say it,” Kelly said. “Let’s let the data speak for itself. What we really need is a comprehensive invasive species master plan for Lake George that says when an invasive species enters, what do we do? Here’s the sequence of mitigation actions. I’m hoping this data will bring us together so we look at the facts and have a discussion about what is a good master plan for Lake George.”